How Has The Composition Of The Labor Force Changed From 1900 To 2011?

Rise female labor force participation has been one of the most remarkable economic developments of the last century. In this entry nosotros present the key facts and drivers behind this important modify.

Hither is an overview of some of the main points nosotros cover below:

All our charts on Women'due south employment

Historical perspective

Female participation in labor markets grew remarkably in the 20th century

The 20th century saw a radical increase in the number of women participating in labor markets across early-industrialized countries. The following visualization shows this. It plots long-run female participation rates, piecing together OECD information and available historical estimates for a selection of early-industrialized countries.

As we can see, there are positive trends across all of these countries. Notably, growth in participation began at dissimilar points in fourth dimension, and proceeded at different rates; all the same, the substantial and sustained increases in the labor force participation of women in rich countries remains a striking feature of economical and social alter in the 20th century.1

However, this chart likewise shows that in many rich countries – such every bit, for example, the Usa – growth in participation slowed down considerably or even stopped at the plough of the 21st century.2

Married women drove the increase in female labor force participation in rich countries

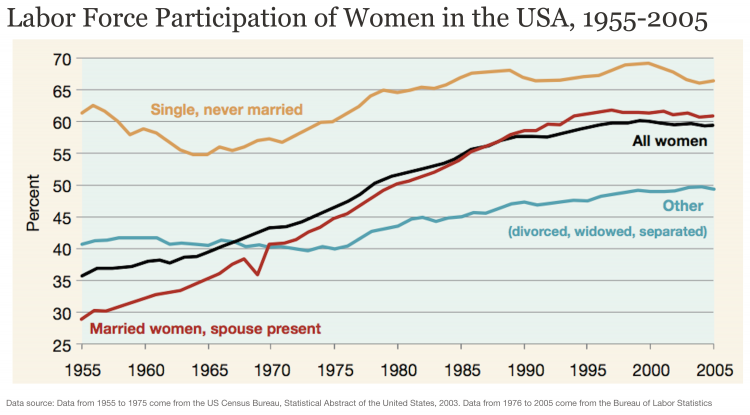

Most of the long-run increment in the participation of women in labor markets throughout the last century is attributable specifically to an increment in the participation of married women.

The following visualization shows the feel of the The states. Information technology plots female labor force participation rates, differentiating by marital status. As tin exist seen, the marked upward trend observed for the full general female population is mainly driven by the tendency amid married women. Heckman and Killingsworth (1986) provide evidence of similar historical trends for the UK, Germany and Canada.three

Labor force participation of women in the The states, past marital status – Engemann & Owyang (2006)4

Higher female labor force participation oftentimes went together with fewer worked hours

The following chart shows average weekly hours worked for women in a choice of OECD countries. Equally nosotros can see, most countries show negative trends, which is consequent with the trends for the population as a whole. Notwithstanding, some of these trends are even so remarkable if we have into account the substantial increase in female person participation taking place at the aforementioned time.

This is an important pattern: At the aforementioned time equally more women in rich countries started participating in labor markets, there was ofttimes a reduction in the average number of hours that women spent at work. Estimates propose that in virtually all cases, the upshot along the all-encompassing margin (participation) was much stronger, and then total amount of female work in labor markets (Hours per female person worker x Number of female person workers) went up.v

Labor force participation

Female participation in labor markets, country past country

The following visualization shows female labor force participation rates, across earth regions.

Past clicking Add state you can add together data for specific countries and regions.

And you lot can meet the modify over fourth dimension by using the time slider beneath the chart.

Around the globe, the participation of women in labor markets has increased in the last decades

In the majority of countries, beyond all income levels the participation of women in labor markets is today higher than several decades agone. The chart shows this, comparing national estimates of female participation rates in 1980 (vertical axis) and the latest bachelor yr (horizontal axis).

The greyness diagonal line has a gradient one, so countries that have seen positive changes towards women appear on the bottom right. As we can meet, well-nigh countries lie on the bottom right, and some are very far below the diagonal line.

The chart shows ILO's 'non-modelled' estimates, which take a college margin of fault simply are available for a longer period. Whenever a country had missing data for 1980 or the latest available year, the closest year with available data is shown (within a 5-twelvemonth window).

For reference, this slope chart plots the aforementioned dataset, but only for countries with observations on 1980 and the latest bachelor year.

Men tend to participate in labor markets more frequently than women

Despite recent growth in female participation rates, men still tend to participate in labor markets more oft than women. The post-obit visualization shows this. It plots the female-to-male ratio in labor force participation rates (expressed in percents). These figures represent to estimates from the International Labour Arrangement (ILO). These are 'modelled estimates' in the sense that the ILO produces them after harmonising various information sources to improve comparability beyond countries.

As we can see, the numbers tend to be well beneath 100%, which ways the participation for women tends to be lower than participation for men. However differences are outstanding: In countries such as Syria or Algeria, the relationship is below 25%. In contrast, in Laos, Mozambique, Rwanda, Malawi and Togo, the relationship is close or even slightly above 100% (i.e. in that location is gender parity in labor force participation in these countries).

Female labor force participation varies with age

The adjacent chart compares labor force participation among younger and older women. To exist specific, among women ages 25-34 and 45-54.

Every bit we tin can run across, very few countries lie on the diagonal line, so in most cases female labor forcefulness participation is not abiding beyond age groups.

In some countries participation is higher for younger women, and in some countries information technology is higher for older women. However, there is an interesting design: In countries where female participation in labor markets is by and large low (those at the bottom left), it tends to be the example that participation is much higher among younger women.

Consider Kuwait: The female participation rate is almost 48% if we consider all women; yet the rates for younger and older women are 68% and 34% respectively.

The global expansion of female labor supply has gone together with a increase in the average age of women in the labor force

The visualization shows the historic period distribution of women who are economically active. This nautical chart allows you to explore countries and regions (employ the option labelled 'Change country'), every bit well as relative and accented figures (apply the option labelled 'relative' to change betwixt percentage and number of workers).

As we tin can see, today the number of women in the global labor force who are younger than 25 is slightly less than what it was xv years ago. Yet, the global female person labor force grew by almost 50% over the aforementioned flow.

This shows that the global expansion of female labor supply has gone together with a increment in the boilerplate age of women in the labor force.

In rich countries there has been a steeper increase in the age of women in the labor strength, partly because participation amongst younger women has actually gone downwardly.

Employment

Female employment has grown together with rising female person participation

Labor forcefulness participation comprises both employed and unemployed people searching for piece of work. The chart plots female employment-to-population ratios across the globe (national estimates earlier ILO corrections). These figures testify the number of employed women as a share of the total female person population.

Every bit we can meet, the trends are consistent with those for labor force participation: In the flow 1980-2016, the majority of countries saw an increase in the share of women who are employed. This is what we would wait – it means that, more often than not, the participation of women in the labor market place was driven by employment, rather than unemployment.

The representation of women in employment across different economic sectors

The post-obit chart plots the share of women in dissimilar economical sectors, country by state.

As we can come across, in near countries there is 'occupational segregation': Women tend to be disproportionately concentrated in certain types of jobs. And in some cases (e.g. Italy in the chart), these patterns of segregation have get more pronounced in recent decades.

As nosotros discuss in another web log post, this likewise has of import consequences for pay differences between men and women.

The sectoral composition of female employment

The chart above shows the gender distribution of sectoral employment. Every bit we signal out above, this allows us to explore 'occupational segregation'.

Another way to explore segregation patterns is to cut the data the other mode around, and look at the distribution of female employment across sectors. That is, the sectoral composition of female employment, rather than the gender composition of sectoral employment.

This tin can be seen in the charts for industry, services and agronomics.

All over the world men are more likely to work in industry than women (nigh countries lie beneath the diagonal line). And women tend to work more often than men in services.

The pattern for services is too interesting considering it shows some important regional differences: In many low-income countries where the service sector is small in relative terms (i.e. countries in the bottom left, where both male and female employment in services is low), the blueprint is reversed, and men tend to work more than often in services than women. Republic of india is an of import example in indicate.

Informal work & unpaid care work

Women often work in the informal economic system

The following chart shows the share of women employed in the informal economic system, equally a share of all women who are employed in not-agronomical economical activities.

As nosotros can see, a large function of female person employment around the globe takes place in the breezy economy. In fact, in many low and middle income countries, the vast bulk of women engaged in paid work are in the breezy economy. For women in Republic of uganda, for example, nigh 95% of paid work exterior agriculture is informal. In Greece, the corresponding figure is close to 4%.

How practise the figures for women compare to those for men? In the majority of countries women tend to work more frequently in the breezy economy than men. And information technology is likely that this gender divergence would be larger if we deemed for the informal agronomical economy, for which data is non bachelor.

Women spend substantially more fourth dimension than men on unpaid care work

Unpaid care work at domicile is an important activity in which women tend to spend a pregnant corporeality of time – and, every bit we discuss below, it is an activity that is typically unaccounted for in labor supply statistics. In the adjacent nautical chart we show just how skewed the gender distribution of unpaid care work in the household is.

The chart shows the female person-to-male ratio of fourth dimension devoted to unpaid services provided within the household, including care of persons, housework and voluntary community piece of work. You tin can add together countries using the button labeled ' Add land '. And you lot can click on the 'Map' tab to become a cross-country overview.

Gender differences in time devoted to unpaid care work cut beyond societies: All over the world, women spend more than time than men on these activities. All the same in that location are clear differences when it comes to the magnitude of these gender gaps. At the low end of the spectrum, in Uganda women work 18% more than men in unpaid care activities at home. While at the contrary end of the spectrum, in countries such equally Bharat, women work 10 times more than than men on these activities.

A report from the OECD shows a breakdown of time spent on unpaid care work past gender and region.6

Unemployment

In most countries the unemployment rate is higher for women than for men

The scatter plot compares unemployment rates among men and women. Every bit we tin can see, in almost countries unemployment rates are higher for women than for men.

But the difference of the unemployment rates depends on the overall unemployment rate in the state:

On the left-hand side of the chart we can come across that most countries prevarication close to the diagonal line mark gender parity. This ways that in countries with mostly low unemployment rates, the gender differences in unemployment are non very large.

Even so, on the correct-hand side of the chart, most countries lie significantly above the diagonal line – so in countries where unemployment is more common, women tend to be disproportionately affected.

Countries with very low female labor strength participation tend to also have high female unemployment

The map shows unemployment rates for women across the globe. As we tin can meet, the highest female unemployment rates correspond to the countries with the everyman female labor force participation, notably in N Africa and the Middle East.

Closely related to this is the fact that in many countries with low female labor force participation, people think that whenever jobs are scarce, men should have more than correct to a chore.

Strikingly, in India, 84% of the survey respondents agreed with the argument: "When jobs are deficient, men should take more right to a job than women."

As we have already mentioned to a higher place, women all over the world tend to spend a substantial amount of time on unpaid care work, which work falls exterior of the traditional economic production boundary. In other words, women often work but are non regarded as 'economically active' for the purpose of labor supply statistics.

This type of non-marketplace work can be time consuming. Information technology is therefore not surprising that the factors driving an increase in female labor supply – whether they are improvements in maternal health, reductions in the number of children, childcare provision, or gains in household engineering science – all impact unpaid care work.

Below we discuss each of these factors, the underlying importance of social norms, and a 'larger picture' view of long-term structural change.

Maternal health

Motherhood – pregnancy, childbirth, and the flow after childbirth – imposes a substantial burden on women's health and time. This, in turn, can take a meaning impact on women's ability to participate in the labor force.

Researchers Alabanesi and Olivetti (2016)7 estimate that in 1920, an American woman could lose on average ii.31 years per pregnancy due to disabilities associated with maternal conditions. Past 1960, that figure had declined to 0.17. The researchers show that the historical pass up in the brunt of maternal conditions and the introduction of infant formula contributed to the rise in married women'due south labor force participation between 1930 and 1960 in the US.

The chart illustrates the human relationship between maternal mortality and female person labor strength participation in the US. Every bit we can see, falling maternal mortality is accompanied by rising female person labor force participation.

Fertility

On average, mothers around the world continue to spend more than fourth dimension on childcare than fathers. Because of this, lower fertility – fewer children per woman – can free up women'southward time and contribute to an increase in female person labor forcefulness participation.

A number of studies have established causal evidence of this by considering exogenous changes in family size and their bear on on labor marketplace outcomes.viii

Fifty-fifty more importantly, inquiry past Goldin and Katz (2002)9 shows that increasing women'due south command over their reproductive choices contributes to altering their career and marriage choices by eliminating the risk of pregnancy and encouraging career investment.

The visualization shows the boilerplate annual modify in fertility and female labor strength participation across the world, from 1960 to the most recent year. Despite some outliers and some clear differences by region, nosotros tin can see that almost countries are in the upper-left quadrant – that is, in most countries female labor force participation has gone upward at the same time that fertility has gone downward.

Childcare policies

Because women on average however spend more time on childcare than men, family oriented policies – such as childcare back up – tin brand employment more than uniform with motherhood.

A natural experiment from Canada provides causal evidence for this. In 1997, the provincial government of Quebec introduced a generous subsidy for childcare services. Researchers Lefebvre and Merrigan found that this policy had substantial labor supply furnishings on the mothers of preschool children, increasing participation both among well-educated and less well-educated mothers.10

In the nautical chart we show that female employment, measured as the employment-to-population ratios for women fifteen+, tends to be higher in countries with higher levels of public spending on family benefits (i.e. child-related cash transfers to families with children, public spending on services for families with children, and fiscal support for families provided through the revenue enhancement system, including tax exemptions).

Labor-saving consumer durables

The introduction of labor-saving consumer durables such as washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and other fourth dimension-saving products has reduced the corporeality of fourth dimension required for household chores – something that women on average spend more fourth dimension than men on.

Greenwood et al. (2005)11 present show for this, arguing that such innovations can assist explain the ascent in married female labor force participation in the US between 1900 and 1980.

The nautical chart provides a sense of perspective on the impact that consumer durables can accept on the domestic work done by women all over the world.

Social norms

Social norms and civilisation influence the way we see the world and our role in it. To this stop, at that place is little doubt that the gender roles assigned to men and women are in no small part socially constructed.12

Recently, scholars accept taken an interest in trying to determine when and how gender roles first emerged historically. And while theories about the origin of gender roles are certainly an interesting strand of research, our recent and fifty-fifty electric current practices show that these roles continue to persist with the help of institutional enforcement.thirteen Goldin (1988)14, for instance, shows that "matrimony bars" in the 1800s and 1900s prohibited married women from working in didactics and clerical jobs – occupations that would become the most ordinarily held among them after 1950.

Where are there restrictions on the jobs women are allowed to have?

Every bit we run across in the map, barriers to women entering the labor force proceed to exist across many countries today. The data in this map, which comes from the Earth Banking concern's World Development Indicators, provides a measure out of whether there are any specific jobs that not-pregnant and non-nursing women are non allowed to perform.

So, for example, a country might be coded as "No" if women are only allowed to work in certain jobs inside the mining manufacture, such as health care professionals within mines, but not as miners.

Public stance about working women

Only even after explicit barriers are lifted and legal protections put in their place, bigotry and bias tin continue to exist in less overt ways. Goldin and Rouse (1997)15, for example, look at the adoption of "blind" auditions past orchestras, and show that by using a screen to conceal the identity of a candidate, impartial hiring practices increased the number of women in orchestras by 25% between 1970 and 1996.

The chart illustrates public opinion in the United states on whether married women should work. At the stop of World War Ii, only xviii% of people in the US thought and so. Female labor supply started to increase in the US alongside changing social norms: as more than people approved of married women working, female labor force participation grew – and equally approval stagnated in the 90s, so did labor forcefulness participation.

Structural changes of the economy

The chart plots female labor strength participation rates by national income. As we can see, female labor force participation is highest in some of the poorest and richest countries in the world, while information technology is lowest in countries with incomes somewhere in between. In other words: in a cross-section, the relationship betwixt female participation rates and Gross domestic product per capita follows a U-shape.

In depression-income countries, where the agricultural sector is particularly of import for the national economy, nosotros see that women are heavily involved in product, primarily as family workers. Under such circumstances, productive and reproductive work is non strictly delineated and can be more easily reconciled. With technological alter and market expansion, still, work becomes more capital intensive and is oftentimes physically separated from the home. In middle income countries, there is an observed social stigma fastened to married women working and "women's work is often implicitly bought past the family unit, and women retreat into the home, although their hours of piece of work may non materially change."16

With sustained development, women make educational gains and the value of their time in the market increases alongside the demand-side pull from growing service industries. This means that in high income countries, the rise in female labor strength participation is characterized past women gaining the option of moving into paid, often white-collar work, while the opportunity price of exiting the workforce for childcare rises.17

For some loftier-income countries, this U-shape pattern has as well been observed over fourth dimension. For case, long-run evidence from Italy shows that female person labor force participation was actually everyman around 1960, and is today nonetheless lower than in the period earlier the 2d Globe War.18

Definitions & Measurement

Conceptual issues with the definition of "piece of work"

Throughout this entry, labor forcefulness participation is divers equally being 'economically active'. But what does that actually mean? Being able to respond this question is crucial to agreement female labor supply, since women typically invest time on productive activities that exercise not count equally 'market labor'.

From a conceptual point of view, people who are economically active are those who are either employed (including role-time employment starting from one hour a week) or unemployed (including anyone looking for job, even if it is for the first fourth dimension). Students who practice not have a job and are non looking for one, are non economically active.

In the guidelines stipulated by the ILO, 'employment' also includes self-employment, which ways that in principle, the labor force includes anyone who supplies labor for the production of economical goods and services, independently of whether they do then for pay, turn a profit or family gain. This nautical chart from the ILO shows an overview of what counts and what doesn't towards producing 'economic goods and services'.xix

Loosely speaking, the guidelines stipulate that unpaid activities should be excluded if they lead to services or goods produced and consumed within the household (and they are not the prime contribution to the full consumption of the household).20 This often means excluding unpaid work on things similar "Preparation and serving of meals"; "Intendance, training and instruction of children"; or "Cleaning, decorating and maintenance of the dwelling".

The implication, and so, is that fifty-fifty if the guidelines are followed closely to include all possible forms of economic activities, even in the informal sector, there will all the same exist an important number of 'working women' who are excluded from the labor force statistics. And these exclusions are even more than salient if we consider that in many countries actual measurement deviates from the guidelines.

There is an ongoing debate concerning the omission of unpaid care piece of work from official labor statistics. The 2009 Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Committee on the Measurement of Economic Performance And Social Progress puts it this way:21

There have been large changes in the functioning of households and the society. For case, many of the services that people received from their family in the by are at present purchased on the market. This shift translates into a rise of income, equally measured in the national account, and this may give a false impression of a change in living standards, while it just reflects a shift from not-marketplace to marketplace provision of services. A shift from private to public provision of a detail product should not touch on measured output. By the same token, a shift of production from marketplace to household production or vice versa, should not affect measured output. In practice, this invariance principle is not bodacious by current conventions on the measurement of household services.

A 2014 OECD publication titled "Unpaid Intendance Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes", echoes the findings of the 2009 Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission, and recommends introducing Household Satellite Accounts, which could mensurate unpaid intendance work via Time Use Surveys. They stress that disregarding unpaid care work can significantly misestimate households' material well-being. According to some studies, if included, unpaid intendance work would constitute 40% of Swiss Gross domestic product and 63% of Indian Gdp.22

Measuring work from survey data

In many countries with poor chapters to produce national statistics, labor force participation is measured from population censuses, rather than from labor forcefulness surveys specially designed for that purpose. The result of this is that labor force statistics often exclude individuals who should be covered by the definitions to a higher place.

Indeed, the statistical series labeled as "ILO modelled" try to overcome some of these limitations by harmonizing the national estimates, to ensure comparability across countries and over fourth dimension by accounting for differences in information source, scope of coverage, methodology, and other state-specific factors. The modelled estimates are based mainly on nationally representative labor force surveys, with other sources (population censuses and nationally reported estimates) used only when no survey data are available.23

Unpaid work is ane of the most important exclusions that arise from measurement limitations. Here, the central point to bear in mind is that the ILO standards do recommend including informal workers, both paid and unpaid, under the economically agile population. In do, however, data collection typically focuses on paid informal employment, mainly outside agriculture. This means that labor forcefulness statistics often practise include cocky-employed workers in their ain informal enterprises (e.g. street food vendors), besides equally persons in breezy employment relationships in formal enterprises (e.g. workers hired by formal enterprises without a formal contract). But they often fail to include unpaid work on activities such every bit subsistence farming.

Historical female person labor force participation estimates

Long (1958)

- Information Source: Long, C. D. (1958) 'The labor force under changing income and employment'. Princeton Academy Press.

- Description of available measures: The measure used in this entry is 'proportion of the female population ages 14 and over that is economically active', even so in that location are diverse other breakdowns available in the source.

- Time span: Bachelor time series vary by state, but roughly 1890-1950

- Geographical coverage: Multiple countries (i.due east.

United states of america, Nifty United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, Canada, Frg, New Zealand) - Link: The data used here is found in Appendix A: tabular array A-two, table A-11, table A-sixteen https://econpapers.repec.org/bookchap/nbrnberbk/long58-ane.htm

Heckman and Killingsworth (1986)

- Information Source: Heckman J. and Killingsworth M. (1986) 'Female Labor Supply: A Survey. in Handbook of Labor Economic science, Book I', Edited past O. Ashenfelter and R. Layard (based on: Dept of Employment and Productivity; Demography 1971: Slap-up Great britain; Census 1981: Great Uk General Tables)

- Description of available measures: Female labor strength participation rates (in percent) by age over time.

- Time span: Bachelor time serial vary by country, but roughly 1890-1981

- Geographical coverage: Multiple countries (i.eastward.

US, Nifty United kingdom, Canada, Deutschland) - Link: The data used here is institute in Table 2.three: http://public.econ.duke.edu/~vjh3/e262p/readings/Killingsworth_Heckman.pdf

OECD labor forcefulness participation by sex activity and age

- Data Source: OECD.Stat

- Clarification of available measures: Proportion of the female population ages 15 and older that is economically active.

- Fourth dimension span: 1960-2016

- Geographical coverage: OECD countries

- Link: http://stats.oecd.org/

Recent female labor force participation estimates

Modeled ILO Estimates: Ratio of female to male labor force participation (published past the World Bank)

- Data Source: ILO (International Labor Organisation) modeled estimates – 'modeled' meaning that the ILO harmonizes diverse information sources such as labor force surveys, censuses, etc., in order to meliorate comparability across countries.

- Description of available measures: Ratio of female to male labor force participation rates (%) – defined as proportion of the population ages fifteen+ that is economically agile.

- Time span: 1990-2016

- Geographical coverage: Global by land

- Link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FM.ZS

Modeled ILO Estimates: Female labor force participation rate (published by the World Bank)

- Data Source: ILO (International Labor Arrangement) modeled estimates – 'modeled' meaning that the ILO harmonizes various data sources such equally labor force surveys, censuses, etc., in order to improve comparability across countries.

- Description of available measures: Proportion of the female population ages 15 and older that is economically agile.

- Fourth dimension span: 1990-2016

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.Iron.ZS

ILO 'Non-modeled' national estimates: Female labor force participation charge per unit (published past the Earth Bank)

- Information Source: ILO (International Labor Organization) national estimates – significant that the ILO has non harmonized national data sources, thus there is a college margin of error while making estimates available for a longer period.

- Description of available measures: Proportion of the female population ages 15 and older that is economically active.

- Time span: 1960-2016

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Link: https://information.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.NE.ZS

OECD average usual weekly hours worked

- Data Source: OECD.Stat

- Description of available measures: Average usual weekly hours worked on the main job, for women ages 15+. Estimates correspond to total alleged employment. This includes part-time and full-time employment, too as self-employment and dependent employment.

- Time bridge: 1976-2016

- Geographical coverage: OECD countries

- Link: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=AVE_HRS#)

ILO 'Not-modeled' national estimates: female employment-to-population ratio (published by the World Depository financial institution)

- Data Source: ILO (International Labor Organization) national estimates – pregnant that the ILO has not harmonized national data sources, thus in that location is a higher margin of error while making estimates available for a longer menstruum.

- Clarification of available measures:Proportion of a country's women fifteen+ who are employed.

- Time bridge: 1960-2016

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Link: https://information.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.TOTL.SP.FE.NE.ZS

Female participation in informal and unpaid work

ILO estimates: Female informal employment (published by the World Bank)

- Data Source: ILO (International Labor Organisation)

- Clarification of available measures: % women in breezy employment (For a definition of what is considered 'informal employment' see here.

- Time span: 2004-2016

- Geographical coverage: Global past land

- Link: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.ISV.IFRM.FE.ZS

OECD estimates: Female to male ratio of fourth dimension devoted to unpaid care work

- Data Source: OECD

- Description of available measures: Female to male ratio of time devoted to unpaid care work. Unpaid intendance piece of work refers to all unpaid services provided within a household for its members, including intendance of persons, housework and voluntary community work.

- Time span: The information is based on national time-employ surveys from the latest available yr/s

- Geographical coverage: OECD countries

- Link: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=GIDDB2014#

Barriers to women working

World Bank: Can nonpregnant and nonnursing women can do the aforementioned jobs as men?

- Data Source: The Globe Banking concern

- Description of bachelor measures: Non-pregnant and not-nursing women can do the same jobs every bit men indicates whether in that location are specific jobs that women explicitly or implicitly cannot perform except in express circumstances. Both partial and full restrictions on women'south piece of work are counted equally restrictions. For example, if women are only allowed to work in certain jobs within the mining manufacture, e.k., as wellness intendance professionals within mines but not equally miners, this is a brake.

- Time span: 2009-2015

- Geographical coverage: Global, by land

- Link: https://information.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.JOB.NOPN.EQ

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-supply

Posted by: smithdecorichiggy.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Has The Composition Of The Labor Force Changed From 1900 To 2011?"

Post a Comment